In a recent TED Talk, Pallotta contends that nonprofit business models should use the same business model tools. They should also employ the same strategies as the for profit industry. The reasoning supporting this conclusion is that NPO’s need to become more competitive to recruit top talent. They should create competitive advantage and generate additive values. These values are wanted by the customers but often available in the individual NPO.

Additive Values

Additive values, and ability, are ultimately provided by the entire not for profit industry. Sharing and coordination of resources becomes the norm. Ultimately no single NPO serves all the need categories belonging to any individual customer or homogeneous group of customers. The largest funder of NPO services is the government.

The values based culture of NPO’s often espouses the belief that employees can be recruited through non-financial incentives. They can be retained and satisfied similarly. This often refers to 1) benefits and 2) holidays (which are financial but benchmarked with ‘competitors’ and so no advantage is leveraged), 3) relationships, 4) opportunities to grow, 5) opportunities for advancement, 6) opportunities to engage novel projects of interest, and 7) frequent celebrations surrounding their/teams successes.

Barriers

The challenge is that NPO’s often struggle with the same non-functional attitudes. These include personalities and behaviors seen in the for-profit world. They face additional barriers to discuss these non-functional characteristics. Low salaries trap the NPO into employing much more entry-level staff. They must rebuild the NPO culture to align with and support the non-financial incentives.

The reality that NPO services requires the inclusion of relationships with other NPO’s has created a culture of collaboration. It also fosters coordination. The value additive mechanisms that are part of the competitive modeling for businesses is largely absent.

Benchmarking

When value is added to the industry it is often matched and benchmarked by adjacent NPO’s. These additive values are included as explicit written expectations. They are also added as non-explicit verbal expectations of the public entity that is contracting with the NPO’s.

Change Triggers

Although NPO’s can compete through size and scope of services these rarely change as a result of internal forces. To acquire salary increases and professional development, one often turns to self-employment. Alternatively, moving on to the next company provides these opportunities. The seven non-financial incentives listed in the paragraph above are poorly leveraged by most NPO’s. This is not enough to gain employee loyalty. It is certainly insufficient to recruit top talent.

The collaboration and coordination conducted in the NPO industry is a necessity. It is not a competitive advantage. The individual NPO can espouse that their partnerships represent additive values unique to the NPO’s expertise. Such partnerships are common and required by service contract.

Structure

The fact that the NPO’s industry, per individual sector, is mostly homogeneous in business structure. It also shows competitive capacity. This homogeneity creates a reinforcing mechanism. This mechanism limits the development of the competencies necessary to consider being more competitive.

This is not to say that competition does not exist; it does exist, both externally and internally. The issue is frequent. It often lacks strategic planning, integration, sustainability, and leverage by the revitalized NPO structures and systems. These acts don’t effectively capitalize on the competitive values they achieve. This statement holds if the values are truly additive and perceived that way by the customer.

The homogeneity of the NPO industry, per individual sector, also creates benchmarks for salaries, benefits, and administrative overhead. The result is that only a small portion of profits can be allocated to financial incentives. These incentives would beneficially impact employee development, recruitment, and retention. This homogeneity also harms competitors in the for-profit NPO industries. These competitors suffer due to the lower benchmarks otherwise common in the industry.

Performance

Even if profits are allowed, they are not often allocated to financial incentives. These incentives do not impact the three employee metrics discussed earlier. A bonus may be provided. However, this does not offset the low salary. Another example is that a bonus may be given. Yet, it does not offset the newly structured lower salary scales. These scales are established to match existing industry benchmarks. They also aim to improve company profits simultaneously.

It is more likely that changes in customers, or losing a customer to a competitor, result from an individual employee. This is rather than a competitive advantage that the other NPO retains. Geography and new ‘needs’ being identified are other factors that influence customer retention. Dissatisfaction, not necessarily associated with any specific externality, is another influence. Changes in the family system and legal entanglements also play a role.

Competitive Advantage

Although competitive advantage could be acquired by an individual NPO that develops a unique set of competencies, it is unlikely. These competencies would not be consistently or adequately leveraged within the existing industry structure. Within the current industry structure, collaboration remains necessary for NPOs to discuss risks. Coordination is also essential to address needs not served by existing service-lines.

Having the ability to find solutions is not the same as being able to champion or implement the solutions. The industry structure leaves little reason for NPO’s to offer better financial incentives. This decision negatively impacts the company’s competitive advantage. In the NPO sector competition, and advantages, are not viewed as desirable.

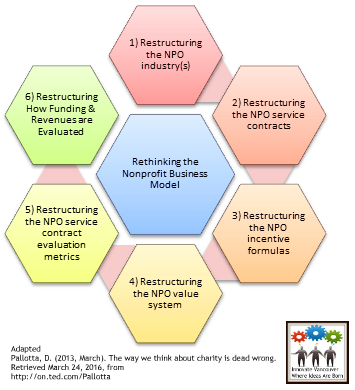

Such solutions might include:

1) Restructuring the NPO industry(s) (to include business modeling)

2) Restructuring the NPO service contracts (to include the budget and KSA requirements)

3) Restructuring the NPO incentive formulas (fully integrated into the Ops plan)

4) Restructuring the NPO value system (to include the recognition that additive value serves the customer and is not just a for-profit value; fully integrated into the Ops plan)

5) Restructuring the NPO service contract evaluation metrics (to include public incentives for delivering targeted outcomes,..i.e., referrals, etc.).

At this current point the above solutions are beyond reach but they shouldn’t be. Many professionals working in the NPO industry(s) recognize the mechanisms that support both the agency and the customer. The challenge is to get NPO’s and the public oversight mechanisms to also recognize the employee.

An Argument for Changing the Model

In the current framework, it would be rare for an existing and satisfied customer to complain. They are generally content with the employees delivering their services. They would not likely argue that these employees, etc., are paid too much. They recognize the value of their services. This is more likely to occur with proposed tax increases. These increases would affect non-customers. It may also occur when a potential customer is denied NPO services due to inadequate financial resources. Another reason could be when “slots” are not available.

When you take care of your employee you are also helping to take care of the customer. Everyone wins. This well-known fact is often dismissed or invalidated in the nonprofit business model. This often occurs through omission. This must first change to allow NPO’s to join competitive processes, practices, and systems.

Travis Barker, MPA GCPM

Innovate Vancouver

Innovate Vancouver is a Technology and Business Innovation Consulting Service located in Vancouver, BC. Contact Innovate Vancouver to help with your new project. Innovate Vancouver also gives back to the community through business consulting services. Contact us for more details.

Reference: